The Power of the Daleks

| 030 – The Power of the Daleks | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who serial | |||

| Cast | |||

Others

| |||

| Production | |||

| Directed by | Christopher Barry | ||

| Written by | David Whitaker Dennis Spooner (uncredited)[1] | ||

| Script editor | Gerry Davis | ||

| Produced by | Innes Lloyd | ||

| Music by | Tristram Cary[a] | ||

| Production code | EE | ||

| Series | Season 4 | ||

| Running time | 6 episodes, 25 minutes each | ||

| Episode(s) missing | All 6 episodes | ||

| First broadcast | 5 November 1966 | ||

| Last broadcast | 10 December 1966 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

The Power of the Daleks is the completely missing third serial of the fourth season of British science fiction television series Doctor Who, which was first broadcast in six weekly parts from 5 November to 10 December 1966. It is the first full story to feature Patrick Troughton as the Second Doctor.

In this serial, the new Doctor (Troughton) and his travelling companions Polly (Anneke Wills) and Ben (Michael Craze) land on the planet Vulcan. There they find an Earth colony, where the lead scientist Lesterson (Robert James) discovers a 200-year-old alien capsule containing three inactive Daleks. Once brought back to life, the Daleks act as the colony's servants, but all they really want is power.

All six episodes of this serial are among the Doctor Who missing episodes. Although audio recordings, still photographs, and clips of the story exist, no full episodes are known to have survived. In 2016, a full-length animated reconstruction of The Power of the Daleks was released to coincide with the serial's fiftieth anniversary, with an updated "special edition" following in 2020.

Plot

[edit]Synopsis

[edit]After transforming, the new Doctor regains consciousness, sets the TARDIS in flight, and appears to deliberately misunderstand direct questions from Ben and Polly. Ben suspects him to be an imposter, though Polly is willing to believe he is the same man. The TARDIS lands on the planet Vulcan, where the Doctor witnesses the murder of an examiner from Earth, sent to inspect the planet's colony. The Doctor, using the dead man's badge, pretends to be the examiner. A security team, led by Bragen, escorts the Doctor, Ben and Polly to the colony, where they meet the governor, Hensell, and his deputy Quinn. There are indications of a rebel faction that Hensell does not take seriously.

The Doctor and his companions learn of a two-century-old capsule discovered by the colony's scientist, Lesterson. The Doctor sneaks into the laboratory, with Ben and Polly following, where they discover two Daleks inside the capsule, with a third missing. The group is discovered by Lesterson; the Doctor asks him where the third Dalek is and the scientist reports that he hid what he assumed was a machine, with the intention to reactivate it. Later, Lesterson and his assistants manage to revive the Dalek and Lesterson removes its gun stick after one of the assistants, Resno, is killed.

Quinn, revealed as the one who summoned the examiner, is accused by Bragen of sabotage and is arrested, with his position then assigned to Bragen. The Doctor, Ben and Polly are present during these events, during which Lesterson arrives with the reactivated Dalek, which feigns loyalty. The Doctor remains suspicious and verbally hostile to the Dalek, who recognises the Doctor, finally convincing Ben that he is the same man. Lesterson reactivates the other two Daleks and removes their guns. The three Daleks are revealed to be secretly planning to take over the colony.

The Doctor's warning that the Daleks are secretly reproducing is ignored and he and Ben are arrested by Bragen, who knows the Doctor is not the examiner: Bragen is the examiner's killer. Polly is kidnapped by the rebels. Bragen, secretly the leader of the rebels, executes his coup d'état. He has a rearmed Dalek kill Hensell and then decides to kill off the rebels.

Inside the capsule, Lesterson discovers a secret production line mass-producing Daleks, and he loses his sanity. The new Daleks are deployed and a violent battle ensues. The Doctor, Quinn, Ben and Polly escape imprisonment and join the struggle. During the battle, Lesterson and many other colonists are killed by the Daleks. The Doctor finally destroys the Daleks by turning their own power source against them. Bragen is shot by one of the surviving rebels as he attempts to kill Quinn, who becomes the new governor. As the Doctor returns to the TARDIS with his companions, a damaged Dalek stands motionless; as the TARDIS dematerializes, the Dalek's eyestalk moves.

Continuity

[edit]The Power of the Daleks is the first Doctor Who serial to discuss the concept of regeneration. The start of the first episode follows on directly from final scene of the preceding serial, The Tenth Planet, in which Doctor is seen transforming from his previous incarnation. In this first episode, the process is not referred to as "regeneration", but the Doctor, prompted by Ben, states that he has been "renewed". The Doctor also remarks that the process is "part of the TARDIS. Without it, I couldn't survive". The Doctor's clothing also changes as a result of the process.[2]

As the Doctor recovers from his transition, he rummages in a chest of artefacts and discovers Saladin's dagger, referencing the earlier serial, The Crusade (1965). When he looks in a mirror, he briefly sees the image of the First Doctor's face.[2]

Production

[edit]Conception and writing

[edit]

The Power of the Daleks is the first serial to star Patrick Troughton, following the first regeneration of the Doctor, which was a solution proposed by producer Innes Lloyd to account for the departure of original Doctor, William Hartnell.[3] Hartnell was known to be difficult, particularly after the original production team left in 1965; arguments over the direction of the show were common by late 1965 with then-producer John Wiles, and Wiles unsuccessfully tried to replace him.[3] Wiles' successor Innes Lloyd, while having a more positive relationship with Hartnell, advised the actor to leave with approval of the BBC's head of drama series Shaun Sutton.[3] Hartnell decided to leave earlier than contracted on 16 July 1966.[3] BBC memos indicate the Doctor's regeneration was meant to be a "horrifying" metaphysical change. The producers compared it to the hallucinogenic drug LSD, which had the side-effect of "hell and dank horror".[4] Story editor Gerry Davis was inspired by the change in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[5] Polly and Ben were written as initially distrustful of the Doctor, mirroring the audience's likely reaction.[6]

For Patrick Troughton's debut story as the Doctor, the production team decided to re-introduce the Daleks, last seen in the 1965-66 serial The Daleks' Master Plan. Daleks were already an established enemy, popular with audiences, and as critic John Kenneth Muir has noted, while the Doctor had changed significantly with the introduction of a new lead actor, "the producers took no chances" with a serial centred on such a familiar foe as Daleks.[7] The Daleks also allowed the Doctor and the audience, who knew the Daleks were evil, to be a step ahead in the story than the Vulcan characters, allowing for suspense.[6]

Terry Nation, creator of the Daleks, was too busy with The Baron to write the serial and gave permission for another writer to write the Daleks.[8] The serial was written by David Whitaker, the series' original story editor, with uncredited rewrites by his successor, Dennis Spooner.[1][6] Nation discussed possibilities of the Daleks' usage with Whitaker.[8] Spooner's rewrites were focused on characterizing this new Doctor,[6] which Whitaker initially left vague,[9] and he and Davis were unavailable for rewrites when they were requested by Doctor Who co-creator Sydney Newman.[10] Director Christopher Barry had previously worked with Troughton; he believes this led to him being tapped for the job, his fifth serial for the programme.[6] Working titles for this story included The Destiny of Doctor Who,[3] and the third episode was subtitled Servants of Masters in the rehearsal script.[11] Whitaker delivered the scripts between 25 July and 5 September 1966, with his revisions to the last three episodes completed between 20 and 23 September.[9] Spooner's rewrites for the first two episodes were delivered 13 October.[10]

Casting and characters

[edit]

Producer Innes Lloyd and the BBC's head of drama serials, Shaun Sutton, had their sights set on Troughton as the successor for Hartnell; Sutton had been a drama student with Troughton and also directed him.[12] Troughton initially committed to five serials on 2 August 1966, with the press alerted to Hartnell's departure on 5 August,[8] and the story breaking 2 September.[9] This was also when Wills and Craze learned who would be playing Hartnell's successor.[9] Co-creator of Doctor Who, Sydney Newman, described the new Doctor's look and performance as "cosmic hobo."[6][5] Story editor Gerry Davis attributed the "wild" hair and "worse for wear" clothes as a "legacy" from the Doctor's "metaphysical change."[13] Davis also described the Doctor as "vital and forceful," "a positive man of action" but also capable of behaving "like a skilled chess player," with "humour and wit" and "an overwhelmingly thunderous rage."[13] Troughton preferred the comedic approach to the Doctor.[10] It was Troughton's idea to play the recorder, which he had taught himself.[6][5] The character's original costuming including a dark Harpo Marx-like wig, but this was received as too silly by his co-stars.[14]

The Dalek voices were recorded by Peter Hawkins on 12 September; this was the first serial he recorded the villains without David Graham.[15] Bernard Archard, who played Bragen, had worked with Barry before.[6] He returned in Pyramids of Mars (1975) as a different character.[16] Peter Bathurst returned in The Claws of Axos (1971).[17] Robert James returned in The Masque of Mandragora (1976).[18] Edward Kelsey had appeared in The Romans (1965)[19] and would return in The Creature from the Pit (1979).[20]

Design and filming

[edit]This was the first Doctor Who serial for designer Derek Dodd. He was inspired by the films Metropolis and Things to Come.[6] The landscape of Vulcan seen through Lesterson's lab window was a photo of a stock steel factory in Sheffield and was inspired by Forbidden Planet.[6] Dry ice and painted backdrops were used to depict Vulcan.[21] To accommodate the Daleks, the capsule set included ramps and rounded doorways they could fit through.[6] The Daleks used in the episode were modified and reassembled from two used in The Daleks (1963-64), one in The Dalek Invasion of Earth (1964), and a "stunt" prop from The Chase (1965).[22] About ten photographic blow-ups on hardboard depicting Daleks were used for the Episode Five cliffhanger.[23] For the Dalek production line, Dodd created a miniature of the set, and the production actually used the BBC's own Dalek toys, although altered to match the ones in the episode.[6] Barry liked to shoot the Daleks with an "over the shoulder" shot, showing their power.[6] The serial also used an inlay shot with a circular mask on the camera to shoot from the Daleks' point-of-view.[21]

Pre-filming, which included the miniature Dalek production line sequence, took place at Ealing Studios from 26 to 28 September 1966.[22] Filming was delayed by one week due to Spooner's rewrites.[10] The episodes were taped for six consecutive Saturdays, beginning on 22 October and finishing 26 November.[24][25] Some filming and rehearsals overlapped with the following serial, The Highlanders.[26] Anneke Wills was on holiday and therefore does not appear in episode four.[1] Similarly, Michael Craze was absent for episode five, but he still filmed for The Highlanders earlier in the week.[26] Episode 6 was recorded using the 625-line system before the official switchover, although it was telerecorded onto 35mm film, instead of videotape.[1]

To offset costs, Tristram Cary's musical cues were re-used from The Daleks (1963-1964) and The Daleks' Master Plan (1965-1966).[6] Cary was not credited at the end of the first two episodes by mistake.[21] 36 bands of sounds composed by Brian Hodgson at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop were also created for the serial.[15]

Broadcast and reception

[edit]| Episode | Title | Run time | Original air date | UK viewers (millions) [27] | Appreciation Index [27] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Episode One"† | 25:43 | 5 November 1966 | 7.9 | 43 |

| 2 | "Episode Two"† | 24:29 | 12 November 1966 | 7.8 | 45 |

| 3 | "Episode Three"† | 23:31 | 19 November 1966 | 7.5 | 44 |

| 4 | "Episode Four"† | 24:23 | 26 November 1966 | 7.8 | 47 |

| 5 | "Episode Five"† | 23:38 | 3 December 1966 | 8.0 | 48 |

| 6 | "Episode Six"† | 23:46 | 10 December 1966 | 7.8 | 47 |

A trailer for the serial was broadcast 4 November.[27] The Power of the Daleks was screened in weekly installments from 5 November to 10 December 1966 on BBC1.[27] The serial averaged 7.8 million viewers over its run.[27]

The Power of the Daleks was screened uncensored in Australia on ABC in July and August 1967, and it was repeated in May 1968.[28] It was screened in New Zealand from August to December 1969, and the films were sent to Singapore in 1972.[28]

The films and tapes of the serial were junked by the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s.[29] Some clips survive from various other programmes like Blue Peter, Whicker's World, and Tom Tom, mainly focusing upon the Daleks in Episodes Four, Five, and Six.[27] A trailer for the first episode of the serial that aired the day before the first episode was broadcast was recovered in 2003.[27] In addition some footage filmed in Australia onto 8mm cine film exists, showing brief moments from Episodes One and Two.[27] No footage from Episode Three currently exists.[29]

Reception

[edit]The serial received mixed reception upon broadcast,[6] with Radio Times receiving letters both positive and negative toward the change in the Doctor.[1][30] The BBC's Audience Research Report conducted for the third episode included several complaints that the new Doctor was too clownish; a minority of comments were positive or more forgiving.[1] At the BBC Programme Review on 16 November 1966, Troughton received praise as "excellent," though there were weaker cast members.[31]

Episode Two was the subject of a review from Ann Purser of Television Today, who wrote, "I like the new clownish Dr Who... The character in two episodes is already positively developed and underlined."[31] She also praised the frightening Daleks.[31] Writing in The Listener, JC Trewin wrote before Episode Four that he was "not yet fully adapted to Patrick Troughton".[31] After the serial finished, he wrote, "I continue to sign for William Hartnell (our new man on Vulcan lacks the old caressing note), but all is nearly well when we have the Daleks."[28]

Over time The Power of the Daleks gained a reputation of one of the best Dalek stories.[6] In The Discontinuity Guide (1995), Paul Cornell, Martin Day, and Keith Topping wrote of the story, "The first, and most important, reformatting of Doctor Who's central character is carried out with considerable style."[1][32] In Doctor Who: The Television Companion (1998), David J. Howe, Mark Stammers, and Stephen James Walker wrote that the story's "plotting and dialogue are excellent and the guest characters all very believable and compelling".[1][33] In 2009, Mark Braxton of Radio Times gave the serial five out of five stars, stating "The Power of the Daleks presents us with an intelligent, logical set of scripts that don't over-reach.[30] He noted that the Daleks were "far from one-dimensional" with the serial deploying a claustrophobic setting and memorable moments that eased the transition between Doctors.[30] In 2016, The A.V. Club's Alasdair Wilkins described the early episodes as "downright glacial" in pacing, even taking into account the episodic nature and change in sensibilities over time.[34] He particularly praised the script.[34] In a review of the animated release, IGN's Scott Collura rated the serial an 8.2 out of 10, writing, "The script, meanwhile, while slow and of its time, offers a tale that is relevant even today: Be careful not to selfishly overreach without paying attention to the needs of those around you."[35] James Whitbrook, writing for io9 in 2016, called the story "one of Doctor Who's best adventures ever."[36] He praised the use of the Daleks in the serial because they "are much, much scarier than just mindless, angry weapons," leading to "one of the most satisfying surprises in all of Doctor Who’s lengthy history" that they were in control the whole time.[36] Paul Mount in Starburst, however, described the story as "fairly mundane" and gave the special edition DVD three out of five stars.[37]

In a 2014 poll representing the first 50 years of Doctor Who, Doctor Who Magazine readers voted The Power of the Daleks as the third best 1960s story[38] and 19th overall, up from 21 in 2009.[39] In 2023, The Daily Telegraph ranked the serial the 41st best Doctor Who story.[40] In the Doctor Who Magazine poll for the 60th anniversary in 2023, The Power of the Daleks was voted the third best story of the Second Doctor's tenure.[41] In 2010, Charlie Jane Anders in io9 listed the cliffhanger to the fourth episode—in which the Dalek production line is revealed—as one of the best Doctor Who cliffhangers of all time.[42] She also ranked the serial as the 39th best story and a "classic" in 2015.[43]

Animated version

[edit]Although the video archive of The Power of the Daleks was lost, the BBC commissioned an animated version of the serial in 2016 to mark the 50th anniversary of its original transmission.[44] The animation was produced in black-and-white, to evoke the original 1966 television broadcast, using audio recordings of the original broadcast as a soundtrack, and drawing on film clips and still photographs from the serial. It was directed by Charles Norton, with lead character art by Martin Geraghty, character shading by Adrian Salmon, props by Mike Collins, and background art by Daryl Joyce.[45] Late into production, BBC America began work on a colourised version of the black-and-white animation.[46] In August 2016, the Daily Mirror subsequently revealed that a full animated reconstruction of the serial had been commissioned by the BBC.[47] This was confirmed by the BBC in September 2016.[44]

The animation was released daily on the BBC Store in black-and-white between 5 and 10 November 2016, followed by a colour release of the complete serial on 31 December 2016.[48] In North America, the animation was screened theatrically by Fathom Events on 14 November 2016 and aired on BBC America from 19 November 2016.[49] For the 2020 re-release, the animation was re-composited and some sections were re-animated.[46]

Commercial releases

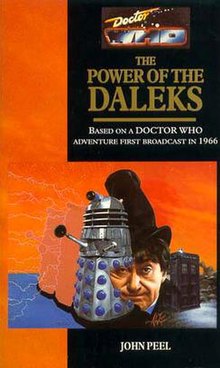

[edit]In print

[edit] | |

| Author | John Peel |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Alister Pearson |

| Series | Doctor Who book: Target novelisations |

Release number | 154 |

| Publisher | Doctor Who Books |

Publication date | 15 July 1993 |

| ISBN | 0-426-20390-9 |

John Peel's novelisation was published by Doctor Who Books, an imprint of Virgin Books, in July 1993.[50] This occurred so late because deals had to be made with the estates of Terry Nation and David Whittaker.[7][50] Peel used Whitaker's draft scripts to write the novelisation and added expanded details of his own.[50] In 1994, Science Fiction Chronicle's Don D'Ammassa reviewed the novelisation as "competently done and entertaining."[51]

The script of this serial, edited by John McElroy, was published by Titan Books in March 1993.[52]

Home media

[edit]The audio soundtrack, recorded directly from television speakers by Graham Strong, survives. The BBC has given it three commercial releases: first, on cassette release with narration by Tom Baker; second, on CD with narration by Anneke Wills; and third, on MP3-CD for the 'Doctor Who: Reconstructed' range, again narrated by Wills and this time including images.[53]

In 2004, all known surviving clips were released on the DVD set Lost in Time.[54] Following this, two more short clips – along with a higher-quality version of one of the extant scenes – were discovered in a 1966 edition of the BBC science series Tomorrow's World; these clips came to light on 11 September 2005 when the relevant section was broadcast as part of an edition of the clip-based nostalgia series Sunday Past Times on BBC Two. They were later included in the documentaries "The Dalek Tapes" (on the DVD of Genesis of the Daleks) and "Now Get out of That" (on the disc containing Terror of the Vervoids, within The Trial of a Time Lord box set).

In the UK, the black and white animation was released on DVD on 21 November 2016,[55] and a Blu-ray/DVD bundle containing the black and white and colour versions in limited steelbook packaging was released in February 2017, making it the first 1960s Doctor Who serial to be released on Blu-ray (although not the first live-action one).[56] A North American DVD containing the black and white and colour versions was released on 31 January 2017.[57] They include clips from the original episodes, the CD-ROM's telesnap reconstruction, a 20-minute documentary covering the original production (Servants and Masters), and an audio commentary; additionally, a 5.1 surround mix of the serial was produced alongside a remaster of the original mono recordings.

An updated version of the animation was released on Blu-ray and DVD on 27 July 2020;[58][59] it also adds newly discovered footage from the original episodes, the narrated cassette version of the serial, two new documentaries, and additional archive content, including an edition of Whicker's World ("I Don't Like My Monsters to Have Oedipus Complexes") and surviving footage of Robin Hood starring Troughton.[46].

Notes

[edit]- ^ Re-use of music recorded for The Daleks and The Daleks' Master Plan

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "BBC – Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – The Power of the Daleks – Details". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020.

- ^ a b Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (31 October 2013). "30. The Power of the Daleks". The Doctor Who Discontinuity Guide. Orion. p. XXX. ISBN 978-0-575-13318-1. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, Mark, ed. (2016). "The Savages, The War Machines, The Smugglers, and The Tenth Planet". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 8, no. 27. London: Panini Comics, Hachette Partworks. p. 119-122.

- ^ "Doctor Who regeneration was 'modelled on LSD trips'". BBC News. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Servants and Masters (DVD). The Power of the Daleks DVD: BBC Worldwide. 21 November 2016.

- ^ a b Muir, John Kenneth (15 September 2015). A Critical History of Doctor Who on Television. McFarland. p. 134-135. ISBN 978-1-4766-0454-1. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth 2016, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth 2016, p. 27.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 21.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 16.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 29.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 24.

- ^ "Pyramids of Mars". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Braxton, Mark (27 October 2009). "The Claws of Axos". Radio Times. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (13 August 2010). "The Masque of Mandragora". Radio Times. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Braxton, Mark (13 December 2008). "The Romans". Radio Times. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (20 February 2011). "The Creature from the Pit". Radio Times. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 30.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 28.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 33.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 2016, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ainsworth 2016, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b The Power of the Daleks - Surviving Footage and Original Trailer (DVD). The Power of the Daleks DVD: BBC Worldwide. 21 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Braxton, Mark (20 April 2009). "The Power of the Daleks". Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). The Discontinuity Guide. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-426-20442-5.

- ^ Howe, David J.; Walker, Stephen James (1998). Doctor Who: The Television Companion. London: BBC Books. pp. 107–111. ISBN 978-1-845-83156-1.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Alasdair (18 November 2016). "A lost Doctor Who classic regenerates into animated form". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Collura, Scott (18 November 2016). "Doctor Who: The Power of the Daleks review". IGN. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b Whitbrook, James (11 November 2016). "'Power of the Daleks' Is an Amazing Moment in Doctor Who History". io9. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Mount, Paul. "Doctor Who - Power of the Daleks Special Edition". Starburst. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Kibble-White, Graham (July 2014). "The Power of the Daleks". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 474. Panini Comics. p. 18.

- ^ "The Results in Full!". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 474. Panini Comics. July 2014. p. 62-63.

- ^ Fuller, Gavin; Hogan, Michael; Gee, Catherine; Lawrence, Ben (2 November 2023). "Doctor Who: the 60 greatest stories and episodes, ranked". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "The DWM 60th Anniversary Poll: The Second Doctor". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 589. Panini Comics. May 2023.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (31 August 2010). "Greatest Doctor Who cliffhangers of all time!". io9. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (17 September 2015). "Every Single Doctor Who Story, Ranked from Best to Worst". io9. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Lost Doctor Who adventure to return in animated form". BBC News. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Guerrier, Simon (December 2016). "Story Preview: The Power of the Daleks". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 505.

- ^ a b c Charles Norton (2 May 2020). "Doctor Who The Power of the Daleks Special Edition – Charles Norton interview" (Interview). Interviewed by Toby Hadoke. Fantom Publishing. Event occurs at 02:44, 20:45 & 24:48. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jefferies, Mark (29 August 2016). "There's some amazing news for Doctor Who fans". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (5 November 2016). "Animated lost Doctor Who story The Power of the Daleks is "enthralling" – and there could be more to come". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company Ltd. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC America Presents 'Doctor Who: The Power of the Daleks' in Theaters Nationwide". BBC America. New Video Channel America, LLC. 2016. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Ainsworth 2016, p. 39.

- ^ D'Ammassa, Don (February 1994). "Review: The Power of the Daleks by John Peel". Science Fiction Chronicle. New York, NY: Algol Press.

- ^ Whitaker, David (March 1993). McElroy, John (ed.). Doctor Who – The Scripts: The Power of the Daleks. London: Titan Books. p. 2. ISBN 1-85286-327-7.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 39-40.

- ^ Ainsworth 2016, p. 40.

- ^ K McEwan, Cameron (26 October 2016). "The Power of the Daleks DVD artwork and extras unveiled". Doctor Who. BBC Studios Distribution. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ K McEwan, Cameron (4 February 2017). "The Power of the Daleks Limited Edition DVD/Bluray steelbook". Doctor Who. BBC Studios Distribution. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (30 January 2017). "DOCTOR WHO's 'Power of the Daleks' DVD is a Complete Picture". Nerdist. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ K McEwan, Cameron (28 April 2020). "The Power of the Daleks – Special Edition with never before seen footage". Doctor Who. BBC Studios Distribution. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Fullerton, Huw (28 April 2020). "Doctor Who: "Updated animation" of Patrick Troughton's Power of the Daleks coming this summer". Radio Times. Immediate Media Company.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ainsworth, John, ed. (2016). "The Power of the Daleks, The Highlanders, The Underwater Menace, and The Moonbase". Doctor Who: The Complete History. Vol. 9, no. 34. London: Panini Comics, Hachette Partworks.

External links

[edit]- The Power of the Daleks at BBC Online

- Photonovel of The Power of the Daleks on the BBC website

- Loose Cannon reconstruction of The Power of the Daleks