Iran

Islamic Republic of Iran | |

|---|---|

| Motto: اَللَّٰهُ أَكْبَرُ Allāhu ʾakbar (Takbir) "God is the Greatest" (de jure) استقلال، آزادی، جمهوری اسلامی Esteqlâl, Âzâdi, Jomhuri-ye Eslâmi "Independence, freedom, the Islamic Republic" (de facto)[1] | |

| Anthem: سرود ملی جمهوری اسلامی ایران Sorud-e Melli-ye Jomhuri-ye Eslâmi-ye Irân "National Anthem of the Islamic Republic of Iran" | |

| Capital and largest city | Tehran 35°41′N 51°25′E / 35.683°N 51.417°E |

| Official languages | Persian |

| Demonym(s) | Iranian |

| Government | Unitary presidential theocratic Islamic republic |

| Ali Khamenei | |

| Masoud Pezeshkian | |

| Mohammad Reza Aref | |

| Legislature | Islamic Consultative Assembly |

| Formation | |

| c. 678 BC | |

| 550 BC | |

| 247 BC | |

| 224 AD | |

| 821 | |

| 1501 | |

| 1736 | |

| 12 December 1905 | |

| 15 December 1925 | |

| 11 February 1979 | |

| 3 December 1979 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi) (17th) |

• Water (%) | 1.63 (as of 2015)[2] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 52/km2 (134.7/sq mi) (132nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (78th) |

| Currency | Iranian rial (ریال) (IRR) |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IR |

| Internet TLD | |

Iran,[a][b] officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI)[c] and also known as Persia,[d] is a country in West Asia. It borders Turkey to the northwest and Iraq to the west, Azerbaijan, Armenia, the Caspian Sea, and Turkmenistan to the north, Afghanistan to the east, Pakistan to the southeast, the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf to the south. With a multi-ethnic population of about 86 million in an area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi), Iran ranks 17th globally in both geographic size and population.[3][8] It is the sixth-largest country entirely in Asia and one of the world's most mountainous countries. Officially an Islamic republic, Iran has a Muslim-majority population. The country is divided into five regions with 31 provinces. Tehran is the nation's capital, largest city and financial centre.

A cradle of civilisation, Iran has been inhabited since the Lower Palaeolithic. The large part of Iran was first unified as a political entity by the Medes under Cyaxares in the seventh century BC, and reached its territorial height in the sixth century BC, when Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid Empire, one of the largest in ancient history. Alexander the Great conquered the empire in the fourth century BC. An Iranian rebellion established the Parthian Empire in the third century BC and liberated the country, which was succeeded by the Sasanian Empire in the third century AD. Ancient Iran saw some of the earliest developments of writing, agriculture, urbanisation, religion and central government. The Sasanian era is considered a golden age in the history of Iranian civilisation. Muslims conquered the region in the seventh century AD, leading to Iran's Islamisation. The literature, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, astronomy and art which had blossomed during the Sasanian era were renewed during the Islamic Golden Age and Persian Renaissance, when a series of Iranian Muslim dynasties ended Arab rule, revived the Persian language and ruled the country until the Seljuk and Mongol conquests of the 11th to 14th centuries.

In the 16th century, the native Safavids re-established a unified Iranian state with Twelver Shi'ism as the official religion. During the Afsharid Empire in the 18th century, Iran was a leading world power, but this was no longer the case after the Qajars took power in the 1790s. The early 20th century saw the Persian Constitutional Revolution and the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty by Reza Shah the Great, who ousted the last Qajar shah in 1925. Attempts by Mohammad Mosaddegh to nationalise the oil industry led to an Anglo-American coup in 1953. After the Iranian Revolution, the monarchy was overthrown in 1979 and the Islamic Republic of Iran was established by Ruhollah Khomeini, who became the country's first Supreme Leader. In 1980, Iraq invaded Iran, sparking the eight-year-long Iran–Iraq War, which ended in stalemate.

Iran is officially governed as a unitary Islamic republic with a presidential system, with ultimate authority vested in a Supreme Leader. The government is authoritarian and has attracted widespread criticism for its significant violations of human rights and civil liberties. Iran is a major regional power, due to its large reserves of fossil fuels, including the world's second largest natural gas supply, third largest proven oil reserves, its geopolitically significant location, military capabilities, cultural hegemony, regional influence, and role as the world's focal point of Shia Islam. The Iranian economy is the world's 23rd-largest by PPP. Iran is a founding member of the United Nations, OIC, OPEC, and ECO as well as a current member of the NAM, SCO, and BRICS. Iran is home to 28 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the 10th highest in the world, and ranks 5th in Intangible Cultural Heritage, or human treasures.

Etymology

The term Iran 'the land of the Aryans' derives from Middle Persian Ērān, first attested in a 3rd-century inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam, with the accompanying Parthian inscription using Aryān, in reference to the Iranians.[9] Ērān and Aryān are oblique plural forms of gentilic nouns ēr- (Middle Persian) and ary- (Parthian), deriving from Proto-Iranian language *arya- (meaning 'Aryan', i.e. of the Iranians),[9][10] recognised as a derivative of Proto-Indo-European language *ar-yo-, meaning 'one who assembles (skilfully)'.[11] According to Iranian mythology, the name comes from Iraj, a legendary king.[12]

Iran was referred to as Persia by the West, due to Greek historians who referred to all of Iran as Persís, meaning 'the land of the Persians'.[13][14][15][16] Persia is the Fars province in southwest Iran, the 4th largest province, also known as Pârs.[17][18] The Persian Fârs (فارس), derived from the earlier form Pârs (پارس), which is in turn derived from Pârsâ (Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿). Due to Fars' historical importance,[19][20] Persia originated from this territory through Greek in around 550 BC,[21] and Westerners referred to the entire country as Persia,[22][23] until 1935, when Reza Shah requested the international community to use its native and original name, Iran;[24] Iranians called their nation Iran since at least 1000 BC.[17] Today, both Iran and Persia are used culturally, while Iran remains mandatory in official use.[25][26][27][28][29]

The Persian pronunciation of Iran is [ʔiːˈɾɒːn]. Commonwealth English pronunciations of Iran are listed in the Oxford English Dictionary as /ɪˈrɑːn/ and /ɪˈræn/,[30] while American English dictionaries provide pronunciations which map to /ɪˈrɑːn, -ˈræn, aɪˈræn/,[31] or /ɪˈræn, ɪˈrɑːn, aɪˈræn/. The Cambridge Dictionary lists /ɪˈrɑːn/ as the British pronunciation and /ɪˈræn/ as the American pronunciation. Voice of America's pronunciation guide provides /ɪˈrɑːn/.[32]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (September 2024) |

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilisations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to 4000 BC.[33] The western part of the Iranian plateau participated in the traditional ancient Near East with Elam (3200–539 BC), and later with other peoples such as the Kassites, Mannaeans, and Gutians. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel called the Persians the "first Historical People".[34] The Iranian Empire began in the Iron Age with the rise of the Medes, who unified Iran as a nation and empire in 625 BC.[35] The Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), founded by Cyrus the Great, was the largest empire the world had seen, spanning from the Balkans to North Africa and Central Asia. They were succeeded by the Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Empires, who governed Iran for almost 1,000 years, making Iran a leading power once again. Persia's arch-rival during this time was the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine Empire.

Iran endured invasions by the Macedonians, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols. Despite these invasions, Iran continually reasserted its national identity and developed as a distinct political and cultural entity. The Muslim conquest of Persia (632–654) ended the Sasanian Empire and marked a turning point in Iranian history, leading to the Islamisation of Iran from the eighth to tenth centuries and the decline of Zoroastrianism. However, the achievements of prior Persian civilisations were absorbed into the new Islamic polity. Iran suffered invasions by nomadic tribes during the Late Middle Ages and early modern period, negatively impacting the region.[36] Iran was reunified as an independent state in 1501 by the Safavid dynasty, which established Shia Islam as the empire's official religion,[37] marking another turning point in the history of Islam.[38] Iran functioned again as a leading world power, especially in rivalry with the Ottoman Empire. In the 19th century, Iran lost significant territories in the Caucasus to the Russian Empire following the Russo-Persian Wars.[39]

Iran remained a monarchy until the 1979 Iranian Revolution, when it officially became an Islamic republic on 1 April 1979.[40][41] Since then, Iran has experienced significant political, social, and economic changes. The establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran led to the restructuring of its political system, with Ayatollah Khomeini as the Supreme Leader. Iran's foreign relations have been shaped by the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), ongoing tensions with the United States, and its nuclear programme, which has been a point of contention in international diplomacy.

Since the 1990s

In 1989, Akbar Rafsanjani concentrated on a pro-business policy of rebuilding the economy without breaking with the ideology of the revolution. He supported a free market domestically, favouring privatisation of state industries and a moderate position internationally. In 1997, Rafsanjani was succeeded by moderate reformist Mohammad Khatami, whose government advocated freedom of expression, constructive diplomatic relations with Asia and the European Union, and an economic policy that supported a free market and foreign investment.

The 2005 presidential election brought conservative populist and nationalist candidate Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to power. He was known for his hardline views, nuclearisation, and hostility towards Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UK, the US and other states. He was the first president to be summoned by the parliament to answer questions regarding his presidency.[42] In 2013, centrist and reformist Hassan Rouhani was elected president. In domestic policy, he encouraged personal freedom, free access to information, and improved women's rights. He improved Iran's diplomatic relations through exchanging conciliatory letters.[43] The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was reached in Vienna in 2015, between Iran, the P5+1 (UN Security Council + Germany) and the EU. The negotiations centred around ending the economic sanctions in exchange for Iran's restriction in producing enriched uranium.[44] In 2018, however, the US under Trump Administration withdrew from the deal and new sanctions were imposed. This nulled the economic provisions, left the agreement in jeopardy, and brought Iran to nuclear threshold status.[45] In 2020, IRGC general, Qasem Soleimani, the 2nd-most powerful person in Iran,[46] was assassinated by the US, heightening tensions between them.[47] Iran retaliated against US airbases in Iraq, the largest ballistic missile attack ever on Americans;[48] 110 sustained brain injuries.[49][50][51]

Hardliner Ebrahim Raisi ran for president again in 2021, succeeding Hassan Rouhani.[52] During Raisi's term, Iran intensified uranium enrichment, hindered international inspections, joined SCO and BRICS, supported Russia in its invasion of Ukraine and restored diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia. In April 2024, Israel's airstrike on an Iranian consulate, killed an IRGC commander.[53][54] Iran retaliated with UAVs, cruise and ballistic missiles; 9 hit Israel.[55][56][57] Western and Jordanian military helped Israel down some Iranian drones.[58][59] It was the largest drone strike in history,[60] biggest missile attack in Iranian history,[61] its first ever direct attack on Israel[62][63] and the first time since 1991, Israel was directly attacked by a state force.[64] This occurred during heightened tensions amid the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip. In May 2024, President Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash[65], and Iran held a presidential election in June, when reformist and former Minister of Health, Masoud Pezeshkian, was elected to office.[66][67] On 1 October 2024, Iran launched about 180 ballistic missiles at Israel in retaliation for assassinations of Ismail Haniyeh, Hassan Nasrallah and Abbas Nilforoushan. On 27 October, Israel responded to that attack by strikes on a missile defence system in the Iranian region of Isfahan.[68]

Geography

Iran has an area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi). It is the sixth-largest country entirely in Asia and the second-largest in West Asia.[69] It lies between latitudes 24° and 40° N, and longitudes 44° and 64° E. It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia (35 km or 22 mi), the Azeri exclave of Nakhchivan (179 km or 111 mi),[70] and the Republic of Azerbaijan (611 km or 380 mi); to the north by the Caspian Sea; to the northeast by Turkmenistan (992 km or 616 mi); to the east by Afghanistan (936 km or 582 mi) and Pakistan (909 km or 565 mi); to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and to the west by Iraq (1,458 km or 906 mi) and Turkey (499 km or 310 mi).

Iran is in a seismically active area.[71] On average, an earthquake of magnitude seven on the Richter scale occurs once every ten years.[72] Most earthquakes are shallow-focus and can be very devastating, such as the 2003 Bam earthquake.

Iran consists of the Iranian Plateau. It is one of the world's most mountainous countries; its landscape is dominated by rugged mountain ranges that separate basins or plateaus. The populous west part is the most mountainous, with ranges such as the Caucasus, Zagros, and Alborz, the last containing Mount Damavand, Iran's highest point, at 5,610 m (18,406 ft), which is the highest volcano in Asia. Iran's mountains have impacted its politics and economics for centuries.

The north part is covered by the lush lowland Caspian Hyrcanian forests, near the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. The east part consists mostly of desert basins, such as the Kavir Desert, which is the country's largest desert, and the Lut Desert, as well as salt lakes. The Lut Desert is the hottest recorded spot on the Earth's surface, with 70.7 °C recorded in 2005.[73][74][75][76] The only large plains are found along the coast of the Caspian and at the north end of the Persian Gulf, where the country borders the mouth of the Arvand river. Smaller, discontinuous plains are found along the remaining coast of the Persian Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz, and Gulf of Oman.[77][78][79]

Islands

Iranian islands are mainly located in the Persian Gulf. Iran has 102 islands in Urmia Lake, 427 in Aras River, several in Anzali Lagoon, Ashurade Island in the Caspian Sea, Sheytan Island in the Oman Sea and other inland islands. Iran has an uninhabited island at the far end of the Gulf of Oman, near Pakistan. A few islands can be visited by tourists. Most are owned by the military or used for wildlife protection, and entry is prohibited or requires a permit.[80][81][82]

Iran took control of Bumusa, and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs in 1971, in the Strait of Hormuz between the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Despite the islands being small and having little natural resources or population, they are highly valuable for their strategic location.[83][84][85][86][87] Although the United Arab Emirates claims sovereignty,[88][89][90] it has consistently been met with a strong response from Iran,[91][92][93] based on their historical and cultural background.[94] Iran has full-control over the islands.[95]

Kish island, as a free trade zone, is touted as a consumer's paradise, with malls, shopping centres, tourist attractions, and luxury hotels. Qeshm is the largest island in Iran, and a UNESCO Global Geopark since 2016.[96][97][98] Its salt cave, Namakdan, is the largest in the world, and one of the world's longest caves.[99][100][101][102]

Climate

Iran's climate is diverse, ranging from arid and semi-arid, to subtropical along the Caspian coast and northern forests.[103] On the north edge of the country, temperatures rarely fall below freezing and the area remains humid. Summer temperatures rarely exceed 29 °C (84.2 °F).[104] Annual precipitation is 680 mm (26.8 in) in the east part of the plain and more than 1,700 mm (66.9 in) in the west part. The UN Resident Coordinator for Iran, has said that "Water scarcity poses the most severe human security challenge in Iran today".[105]

To the west, settlements in the Zagros basin experience lower temperatures, severe winters with freezing average daily temperatures and heavy snowfall. The east and central basins are arid, with less than 200 mm (7.9 in) of rain and have occasional deserts.[106] Average summer temperatures rarely exceed 38 °C (100.4 °F). The southern coastal plains of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman have mild winters, and very humid and hot summers. The annual precipitation ranges from 135 to 355 mm (5.3 to 14.0 in).[107]

Biodiversity

More than one-tenth of the country is forested.[108] About 120 million hectares of forests and fields are government-owned for national exploitation.[109][110] Iran's forests can be divided into five vegetation regions: Hyrcanian region which forms the green belt of the north side of the country; the Turan region, which are mainly scattered in the centre of Iran; Zagros region, which mainly contains oak forests in the west; the Persian Gulf region, which is scattered in the southern coastal belt; the Arasbarani region, which contains rare and unique species. More than 8,200 plant species are grown. The land covered by natural flora is four times that of Europe's.[111] There are over 200 protected areas to preserve biodiversity and wildlife, with over 30 being national parks.

Iran's living fauna includes 34 bat species, Indian grey mongoose, small Indian mongoose, golden jackal, Indian wolf, foxes, striped hyena, leopard, Eurasian lynx, brown bear and Asian black bear. Ungulate species include wild boar, urial, Armenian mouflon, red deer, and goitered gazelle.[112][113] One of the most famous animals is the critically endangered Asiatic cheetah, which survives only in Iran. Iran lost all its Asiatic lions and the extinct Caspian tigers by the early 20th century.[114] Domestic ungulates are represented by sheep, goat, cattle, horse, water buffalo, donkey and camel. Bird species like pheasant, partridge, stork, eagles and falcons are native.[115][116]

Government and politics

Supreme Leader

The Supreme Leader, "Rahbar", Leader of the Revolution or Supreme Leadership Authority, is the head of state and responsible for supervision of policy. The president has limited power compared to the Rahbar. Key ministers are selected with the Rahbar's agreement and they have the ultimate say on foreign policy.[117] The Rahbar is directly involved in ministerial appointments for Defence, Intelligence and Foreign Affairs, as well as other top ministries after submission of candidates from the president.

Regional policy is directly controlled by the Rahbar, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs' task limited to protocol and ceremonial occasions. Ambassadors to Arab countries, for example, are chosen by the Quds Force, which directly reports to the Rahbar.[118] The Rahbar can order laws to be amended.[119] Setad was estimated at $95 billion in 2013 by Reuters, accounts of which are secret even to the parliament.[120][121]

The Rahbar is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, controls military intelligence and security operations, and has sole power to declare war or peace. The heads of the judiciary, state radio and television networks, commanders of the police and military, and the members of the Guardian Council are all appointed by the Rahbar.

The Assembly of Experts is responsible for electing the Rahbar, and has the power to dismiss him on the basis of qualifications and popular esteem.[122] To date, the Assembly of Experts has not challenged any of the Rahbar's decisions nor attempted to dismiss him. The previous head of the judicial system, Sadeq Larijani, appointed by the Rahbar, said that it is illegal for the Assembly of Experts to supervise the Rahbar.[123] Many believe the Assembly of Experts has become a ceremonial body without any real power.[124][125][126]

The political system is based on the country's constitution.[127] Iran ranked 154th in the 2022 The Economist Democracy Index.[128] Juan José Linz wrote in 2000 that "the Iranian regime combines the ideological bent of totalitarianism with the limited pluralism of authoritarianism".[129]

President

The President is head of government and the second highest-ranking authority, after the Supreme Leader. The President is elected by universal suffrage for 4 years. Before elections, nominees to become a presidential candidate must be approved by the Guardian Council.[130] The Council's members are chosen by the Leader, with the Leader having the power to dismiss the president.[131] The President can only be re-elected for one term.[132] The president is the deputy commander-in-chief of the Army, the head of Supreme National Security Council, and has the power to declare a state of emergency after passage by the parliament.

The President is responsible for the implementation of the constitution, and for the exercise of executive powers in implementing the decrees and general policies as outlined by the Rahbar, except for matters directly related to the Rahbar, who has the final say.[133] The President functions as the executive of affairs such as signing treaties and other international agreements, and administering national planning, budget, and state employment affairs, all as approved by the Rahbar.[134][135]

The President appoints ministers, subject to the approval of the Parliament, and the Rahbar, who can dismiss or reinstate any minister.[136][137][138] The President supervises the Council of Ministers, coordinates government decisions, and selects government policies to be placed before the legislature.[139] Eight Vice Presidents serve under the President, as well as a cabinet of 22 ministers, all appointed by the president.[140]

Guardian Council

Presidential and parliamentary candidates must be approved by the 12-member Guardian Council (all members of which are appointed by the Leader) or the Leader, before running to ensure their allegiance.[141] The Leader rarely does the vetting, but has the power to do so, in which case additional approval of the Guardian Council is not needed. The Leader can revert the decisions of the Guardian Council.[142]

The constitution gives the council three mandates: veto power over legislation passed by the parliament,[143][144] supervision of elections[145] and approving or disqualifying candidates seeking to run in local, parliamentary, presidential, or Assembly of Experts elections.[146] The council can nullify a law based on two accounts: being against Sharia (Islamic law), or being against the constitution.[147]

Supreme National Security Council

The Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) is at the top of the foreign policy decisions process.[148][149][150] The council was formed during the 1989 Iranian constitutional referendum for the protection and support of national interests, the revolution, territorial integrity and national sovereignty.[151] It is mandated by Article 176 of the Constitution to be presided over by the President.[152][153]

The Leader selects the secretary of the Supreme Council, and the decisions of the council are effective after the confirmation by the Leader. The SNSC formulates nuclear policy, and would become effective if they are confirmed by the Leader.[154][155]

Legislature

The legislature, known as the Islamic Consultative Assembly (ICA), Iranian Parliament or "Majles", is a unicameral body comprising 290 members elected for four-years.[156] It drafts legislation, ratifies international treaties, and approves the national budget. All parliamentary candidates and legislation from the assembly must be approved by the Guardian Council.[157][158] The Guardian Council can and has dismissed elected members of the parliament.[159][160] The parliament has no legal status without the Guardian Council, and the Council holds absolute veto power over legislation.[161]

The Expediency Discernment Council has the authority to mediate disputes between Parliament and the Guardian Council, and serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader, making it one of the most powerful governing bodies in Iran.[162][163]

The Parliament has 207 constituencies, including the 5 reserved seats for religious minorities. The remaining 202 are territorial, each covering one or more of Iran's counties.

Law

Iran uses the Sharia law as its legal system, with elements of Civil law. The Supreme Leader appoints the head of the Supreme Court and chief public prosecutor. There are several types of courts, including public courts that deal with civil and criminal cases, and revolutionary courts which deal with certain offences, such as crimes against national security. The decisions of the revolutionary courts are final and cannot be appealed.

The Chief Justice is the head of the judicial system and responsible for its administration and supervision. He is the highest judge of the Supreme Court of Iran. The Chief Justice nominates candidates to serve as minister of justice, and the President selects one. The Chief Justice can serve for two five-year terms.[164]

The Special Clerical Court handles crimes allegedly committed by clerics, although it has taken on cases involving laypeople. The Special Clerical Court functions independently of the regular judicial framework and is accountable only to the Rahbar. The Court's rulings are final and cannot be appealed.[165] The Assembly of Experts, which meets for one week annually, comprises 86 "virtuous and learned" clerics elected by adult suffrage for 8-year terms.

Administrative divisions

Iran is subdivided into thirty-one provinces (Persian: استان ostân), each governed from a local centre, usually the largest local city, which is called the capital (Persian: مرکز, markaz) of that province. The provincial authority is headed by a governor-general (استاندار ostândâr), who is appointed by the Minister of the Interior subject to approval of the cabinet.[166]

Foreign relations

Iran maintains diplomatic relations with 165 countries, but not the United States and Israel—a state which Iran derecognised in 1979.[167]

Iran has an adversarial relationship with Saudi Arabia due to different political and ideologies. Iran and Turkey have been involved in modern proxy conflicts such as in Syria, Libya, and the South Caucasus.[168][169][170] However, they have shared common interests, such as the issue of Kurdish separatism and the Qatar diplomatic crisis.[171][172] Iran has a close and strong relationship with Tajikistan.[173][174][175][176] Iran has deep economic relations and alliance with Iraq, Lebanon and Syria, with Syria often described as Iran's "closest ally".[177][178][179]

Russia is a key trading partner, especially in regard to its excess oil reserves.[180][181] Both share a close economic and military alliance, and are subject to heavy sanctions by Western nations.[182][183][184][185] Iran is the only country in Western Asia that has been invited to join the CSTO, the Russia-based international treaty organisation that parallels NATO.[186]

Relations between Iran and China are strong economically; they have developed a friendly, economic and strategic relationship. In 2021, Iran and China signed a 25-year cooperation agreement that will strengthen the relations between the two countries and would include "political, strategic and economic" components.[187] Iran-China relations dates back to at least 200 BC and possibly earlier.[188][189] Iran is one of the few countries in the world that has a good relationship with both North and South Korea.[190]

Iran is a member of dozens of international organisations, including the G-15, G-24, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, IDA, NAM, IDB, IFC, ILO, IMF, IMO, Interpol, OIC, OPEC, WHO, and the UN, and currently has observer status at the WTO.

Military

The military is organised under a unified structure, the Islamic Republic of Iran Armed Forces, comprising the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, which includes the Ground Forces, Air Defence Force, Air Force, and Navy; the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which consists of the Ground Forces, Aerospace Force, Navy, Quds Force, and Basij; and the Law Enforcement Command (Faraja), which serves an analogous function to a gendarme. While the IRIAF protects the country's sovereignty in a traditional capacity, the IRGC is mandated to ensure the integrity of the Republic, against foreign interference, coups, and internal riots.[191] Since 1925, it is mandatory for all male citizen aged 18 to serve around 14 months in the IRIAF or IRGC.[192][193]

Iran has over 610,000 active troops and around 350,000 reservists, totalling over 1 million military personnel, one of the world's highest percentage of citizens with military training.[194][195][196][197] The Basij, a paramilitary volunteer militia within the IRGC, has over 20 million members, 600,000 available for immediate call-up, 300,000 reservists, and a million that could be mobilised when necessary.[198][199][200][201] Faraja, the Iranian uniformed police force, has over 260,000 active personnel. Most statistical organisations do not include the Basij and Faraja in their ratings report.

Excluding the Basij and Faraja, Iran has been identified as a major military power, owing it to the size and capabilities of its armed forces. It possesses the world's 14th strongest military.[202] It ranks 13th globally in terms of overall military strength, 7th in the number of active military personnel,[203] and 9th in the size of both its ground force and armoured force. Iran's armed forces are the largest in West Asia and comprise the greatest Army Aviation fleet in the Middle East.[204][205][206] Iran is among the top 15 countries in terms of military budget.[207] In 2021, its military spending increased for the first time in four years, to $24.6 billion, 2.3% of the national GDP.[208] Funding for the IRGC accounted for 34% of Iran's total military spending in 2021.[209]

Since the Revolution, to overcome foreign embargoes, Iran has developed a domestic military industry capable of producing indigenous tanks, armoured personnel carriers, missiles, submarines, missile destroyer, radar systems, helicopters, naval vessels, and fighter planes.[210] Official announcements have highlighted the development of advanced weaponry, particularly in rocketry.[211][n 1] Consequently, Iran has the largest and most diverse ballistic missile arsenal in the Middle East and is only the 5th country in the world with hypersonic missile technology.[212][213] It is the world's 6th missile power.[214] Iran designs and produces a variety of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and is considered a global leader and superpower in drone warfare and technology.[215][216][217] It is one of the world's five countries with cyberwarfare capabilities and is identified as "one of the most active players in the international cyber arena".[218][219][220] Iran is an key exporter of arms since 2000s.[221]

Following Russia's purchase of Iranian drones during the invasion of Ukraine,[222][223][224] in November 2023, the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF) finalized arrangements to acquire Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets, Mil Mi-28 attack helicopters, air defence and missile systems.[225][226] The Iranian Navy has had joint exercises with Russia and China.[227]

Nuclear programme

Iran's nuclear programme dates back to the 1950s.[228] Iran revived it after the Revolution, and its extensive nuclear fuel cycle, including enrichment capabilities, became the subject of intense international negotiations and sanctions.[229] Many countries have expressed concern Iran could divert civilian nuclear technology into a weapons programme.[230] In 2015, Iran and the P5+1 agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan on Action (JCPOA), aiming to end economic sanctions in exchange for restriction in producing enriched uranium.[231]

In 2018, however, the US withdrew from the deal under the Trump administration, and reimposed sanctions. This was met with resistance by Iran and other members of the P5+1.[232][233][234] A year later, Iran began decreasing its compliance.[235] By 2020, Iran announced it would no longer observe any limit set by the agreement.[236][237] Progress since then has brought Iran to the nuclear threshold status.[238][239][240] As of November 2023[update], Iran had uranium enriched to up to 60% fissile content, close to weapon grade.[241][242][243][244] Some analysts already regard Iran as a de facto nuclear power.[245][246][247]

Regional influence

Iran's significant influence and foothold, sometimes characterised as the "Dawn of A New Persian Empire."[248][249][250][251] Some analysts associate the Iranian influence to the nation's proud national legacy, empire and history.[252][253][254]

Since the Revolution, Iran has grown its influence across and beyond the region.[255][256][257][258] It has built military forces with a wide network of state and none-state actors, starting with Hezbollah in Lebanon in 1982.[259][260] The IRGC has been key to Iranian influence, through its Quds Force.[261][262][263] The instability in Lebanon (from the 1980s),[264] Iraq (from 2003) [265] and Yemen (from 2014) [266] has allowed Iran to build strong alliances and footholds beyond its borders. Iran has a prominent influence in the social services, education, economy and politics of Lebanon,[267][268] and Lebanon provides Iran access to the Mediterranean Sea.[269][270] Hezbollah's strategic successes against Israel, such as its symbolic victory during the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War, elevated Iran's influence in the Levant and strengthened its appeal across the Muslim World.[271][272]

Since the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the arrival of ISIS in the mid-2010s, Iran has financed and trained militia groups in Iraq.[273][274][275] Since the Iran-Iraq war in 1980s and the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iran has shaped Iraq's politics.[276][277][278] Following Iraq's struggle against ISIS in 2014, companies linked to the IRGC such as Khatam al-Anbiya, started to build roads, power plants, hotels and businesses in Iraq, creating an economic corridor worth around $9 billion before COVID-19.[279] This is expected to grow to $20 billion.[280][281]

During Yemen's civil war, Iran provided military support to the Houthis,[282][283][284] a Zaydi Shiite movement fighting Yemen's Sunni government since 2004.[285][286] They gained significant power in recent years.[287][288][289] Iran has considerable influence in Afghanistan and Pakistan through militant groups such as Liwa Fatemiyoun and Liwa Zainebiyoun.[290][291][292]

In Syria, Iran has supported President Bashar al-Assad;[293][294] the two countries are long-standing allies.[295][296] Iran has provided significant military and economic support to Assad's government,[297][298] so has a considerable foothold in Syria.[299][300] Iran has long supported the anti-Israel fronts in North Africa in countries like Algeria and Tunisia, embracing Hamas in part to help undermine the popularity of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).[301] Iran's support of Hamas emerged more clearly in later years.[302][303][304][305] According to US intelligence, Iran does not have full control over these state and non-state groups.[306]

Human rights and censorship

The Iranian government has been denounced by various international organisations and governments for violating human rights.[308] The government has frequently persecuted and arrested critics of the government. Iranian law does not recognise sexual orientations. Sexual activity between members of the same sex is illegal and is punishable by death.[309][310] Capital punishment is a legal punishment, and according to the BBC, Iran "carries out more executions than any other country, except China".[311] UN Special Rapporteur Javaid Rehman has reported discrimination against several ethnic minorities in Iran.[312] A group of UN experts in 2022 urged Iran to stop "systematic persecution" of religious minorities, adding that members of the Baháʼí Faith were arrested, barred from universities, or had their homes demolished.[313][314]

Censorship in Iran is ranked among the most extreme worldwide.[315][316][317] Iran has strict internet censorship, with the government persistently blocking social media and other sites.[318][319][320] Since January 2021, Iranian authorities have blocked a list of social media platforms; Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, Twitter and YouTube.[321]

The 2006 election results were widely disputed, resulting in protests.[322][323][324][325] The 2017–18 Iranian protests swept across the country in response to the economic and political situation.[326] It was formally confirmed that thousands of protesters were arrested.[327] The 2019–20 Iranian protests started on 15 November in Ahvaz, and spread across the country after the government announced increases in fuel prices of up to 300%.[328] A week-long total Internet shutdown marked one of the most severe Internet blackouts in any country, and the bloodiest governmental crackdown of the protestors.[329] Tens of thousands were arrested and hundreds were killed within a few days according to multiple international observers, including Amnesty International.[330]

Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, was a scheduled international civilian passenger flight from Tehran to Kyiv, operated by Ukraine International Airlines. On 8 January 2020, the Boeing 737–800 flying the route was shot down by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) shortly after takeoff, killing all 176 occupants on board and leading to protests. An international investigation led to the government admitting to the shootdown, calling it a "human error".[331][332] Another Protests against the government began on 16 September 2022 after a woman named Mahsa Amini died in police custody following her arrest by the Guidance Patrol, known commonly as the "morality police".[333][334][335][336]

Economy

As of 2024[update], Iran has the world's 19th largest economy (by PPP). It is a mixture of central planning, state ownership of oil and other large enterprises, village agriculture, and small-scale private trading and service ventures.[337] Services contribute the largest percentage of GDP, followed by industry (mining and manufacturing) and agriculture.[338] The economy is characterised by its hydrocarbon sector, in addition to manufacturing and financial services.[339] With 10% of the world's oil reserves and 15% of gas reserves, Iran is an energy superpower. Over 40 industries are directly involved in the Tehran Stock Exchange.

Tehran is the economic powerhouse of Iran.[340] About 30% of Iran's public-sector workforce and 45% of its large industrial firms are located there, and half those firms' employees work for government.[341] The Central Bank of Iran is responsible for developing and maintaining the currency: the Iranian rial. The government does not recognise trade unions other than the Islamic labour councils, which are subject to the approval of employers and the security services.[342] Unemployment was 9% in 2022.[343]

Budget deficits have been a chronic problem, mostly due to large state subsidies, that include foodstuffs and especially petrol, totalling $100 billion in 2022 for energy alone.[345][346] In 2010, the economic reform plan was to cut subsidies gradually and replace them with targeted social assistance. The objective is to move towards free market prices and increase productivity and social justice.[347] The administration continues reform, and indicates it will diversify the oil-reliant economy. Iran has developed a biotechnology, nanotechnology, and pharmaceutical industry.[348] The government is privatising industries.

Iran has leading manufacturing industries in automobile manufacture, transportation, construction materials, home appliances, food and agricultural goods, armaments, pharmaceuticals, information technology, and petrochemicals in the Middle East.[349] Iran is among the world's top five producers of apricots, cherries, cucumbers and gherkins, dates, figs, pistachios, quinces, walnuts, Kiwifruit and watermelons.[350] International sanctions against Iran have damaged the economy.[351] Iran is one of three countries that have not ratified the Paris Agreement to limit climate change, although academics say it would be good for the country.[352]

Tourism

Tourism had been rapidly growing before the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching nearly 9 million foreign visitors in 2019, the world's third fastest-growing tourism destination.[354][355] In 2022 it expanded its share to 5% of the economy.[356] Iran's tourism experienced a growth of 43% in 2023, attracting 6 million foreign tourists.[357] The government ended visa requirements for 60 countries in 2023.[358]

98% of visits are for leisure, while 2% are for business, indicating the country's appeal as a tourist destination.[359] Alongside the capital, the most popular tourist destinations are Isfahan, Shiraz and Mashhad.[360] Iran is emerging as a preferred destination for medical tourism.[361][362] Travellers from other West Asian countries grew 31% in the first seven months of 2023, surpassing Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.[363] Domestic tourism is one of the world's largests; Iranian tourists spent $33bn in 2021.[364][365][366] Iran projects investment of $32 billion in the tourism sector by 2026.[367]

Agriculture and fishery

Roughly one-third of Iran's total surface area is suited for farmland. Only 12% of the total land area is under cultivation, but less than one-third of the cultivated area is irrigated; the rest is devoted to dryland farming. Some 92% of agricultural products depend on water.[368] The western and northwestern portions of the country have the most fertile soils. Iran's food security index stands at around 96 percent.[369][370] 3% of the total land area is used for grazing and fodder production. Most of the grazing is done on mostly semi-dry rangeland in mountain areas and on areas surrounding the large deserts of Central Iran. Progressive government efforts and incentives during the 1990s, improved agricultural productivity, helping Iran toward its goal of reestablishing national self-sufficiency in food production.

Access to the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman, and many river basins provides Iran the potential to develop excellent fisheries. The government assumed control of commercial fishing in 1952. Expansion of the fishery infrastructure enabled the country to harvest an estimated 700,000 tons of fish annually from the southern waters. Since the Revolution, increased attention has been focused on producing fish from inland waters. Between 1976 and 2004, the combined take from inland waters by the state and private sectors increased from 1,100 tons to 110,175 tons.[371] Iran is the world's largest producer and exporter of caviar, exporting more than 300 tonnes annually.[372][373]

Industry and services

Iran is globally ranked 16th in car manufacturing, ahead of the UK, Italy, and Russia.[375][376] It has outputted 1.188 million cars in 2023, a 12% growth compared to the previous years. Iran has exported various cars to countries such as Venezuela, Russia and Belarus. From 2008 to 2009, Iran leaped to 28th place from 69th in annual industrial production growth rate.[377] Iranian contractors have been awarded several foreign tender contracts in different fields of construction of dams, bridges, roads, buildings, railroads, power generation, and gas, oil and petrochemical industries. As of 2011, some 66 Iranian industrial companies are carrying out projects in 27 countries.[378] Iran exported over $20 billion worth of technical and engineering services over 2001–2011. The availability of local raw materials, rich mineral reserves, experienced manpower have all played crucial role in winning the bids.[379]

45% of large industrial firms are located in Tehran, and almost half of their workers work for government.[380] The Iranian retail industry is largely in the hands of cooperatives, many of them government-sponsored, and of independent retailers in the bazaars. The bulk of food sales occur at street markets, where the Chief Statistics Bureau sets the prices.[381] Iran's main exports are to Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Syria, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, France, Canada, Venezuela, Japan, South Korea and Turkey.[382][383] Iran's automotive industry is the second most active industry of the country, after its oil and gas industry. Iran Khodro is the largest car manufacturer in the Middle East, and ITMCO is the biggest tractor manufacturer. Iran is the 12th largest automaker in the world. Construction is one of the most important sectors in Iran accounting for 20–50% of the total private investment.

Iran is one of the most important mineral producers in the world, ranked among 15 major mineral-rich countries.[384][385] Iran has become self-sufficient in designing, building and operating dams and power plants. Iran is one of the six countries in the world that manufacture gas- and steam-powered turbines.[386]

Transport

In 2011 Iran had 173,000 kilometres (107,000 mi) of roads, of which 73% were paved.[387] In 2008 there were nearly 100 passenger cars for every 1,000 inhabitants.[388] Tehran Metro is the largest in the Middle East,[389][390] it carries more than 3 million passengers daily and in 2018, 820 million trips.[391][392] Trains operate on 11,106 km (6,901 mi) of track.[393] The country's major port of entry is Bandar Abbas on the Strait of Hormuz. Imported goods are distributed through the country by trucks and freight trains. The Tehran–Bandar Abbas railroad connects Bandar-Abbas to the railroad system of Central Asia, via Tehran and Mashhad. Other major ports include Bandar e-Anzali and Bandar e-Torkeman on the Caspian Sea and Khorramshahr and Bandar-e Emam Khomeyni on the Persian Gulf.

Dozens of cities have airports that serve passenger and cargo planes. Iran Air, the national airline, operates domestic and international flights. All large cities have mass transit systems using buses, and private companies provide bus services between cities. Over a million people work in transport, accounting for 9% of GDP.[394]

Energy

Iran is an energy superpower and petroleum plays a key part.[396][397] As of 2023[update], Iran produced 4% of the world's crude oil (3.6 million barrels (570,000 m3) per day),[398] which generates US$36bn[399] of export revenue and is the main source of foreign currency.[400] Oil and gas reserves are estimated at 1.2 trn barrels;[401] Iran holds 10% of world oil reserves and 15% for gas. It ranks 3rd in oil reserves[402] and is OPEC's 2nd largest exporter. It has the 2nd largest gas reserves,[403] and 3rd largest natural gas production. In 2019, Iran discovered a southern oil field of 50 bn barrels[404][405][406][407] and in April 2024, the NIOC discovered 10 giant shale oil deposits, totalling 2.6 bn barrels.[408][409][410] Iran plans to invest $500 billion in oil by 2025.[411]

Iran manufactures 60–70% of its industrial equipment domestically, including turbines, pumps, catalysts, refineries, oil tankers, drilling rigs, offshore platforms, towers, pipes, and exploration instruments.[412] The addition of new hydroelectric stations and streamlining of conventional coal and oil-fired stations increased installed capacity to 33 GW; about 75% was based on natural gas, 18% on oil, and 7% on hydroelectric power. In 2004, Iran opened its first wind-powered and geothermal plants, and the first solar thermal plant began in 2009. Iran is the world's third country to develop GTL technology.[413]

Demographic trends and intensified industrialisation have caused electric power demand to grow by 8% per year. The government's goal of 53 GW of installed capacity by 2010 is to be reached by bringing on line new gas-fired plants, and adding hydropower and nuclear generation capacity. Iran's first nuclear power plant went online in 2011.[414][415]

Science and technology

Iran has made considerable advances in science and technology, despite international sanctions. In the biomedical sciences, Iran's Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics has a UNESCO chair in biology.[416] In 2006, Iranian scientists successfully cloned a sheep at the Royan Research Centre in Tehran.[417] Stem cell research is among the top 10 in the world.[418] Iran ranks 15th in the world in nanotechnologies.[419][420][421] Iranian scientists outside Iran have made major scientific contributions. In 1960, Ali Javan co-invented the first gas laser, and fuzzy set theory was introduced by Lotfi A. Zadeh.[422]

Cardiologist Tofy Mussivand invented and developed the first artificial cardiac pump, the precursor of the artificial heart. Furthering research in diabetes, the HbA1c was discovered by Samuel Rahbar. Many papers in string theory are published in Iran.[423] In 2014, Iranian mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani became the first woman, and Iranian, to receive the Fields Medal, the highest prize in mathematics.[424]

Iran increased its publication output nearly tenfold from 1996 through 2004, and ranked first in output growth rate, followed by China.[425] According to a study by SCImago in 2012, Iran would rank fourth in research output by 2018, if the trend persisted.[426] The Iranian humanoid robot Sorena 2, which was designed by engineers at the University of Tehran, was unveiled in 2010. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has placed the name of Surena among the five most prominent robots, after analysing its performance.[427]

Iran was ranked 64th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[428]

Iranian Space Agency

The Iranian Space Agency (ISA) was established in 2004. Iran became an orbital-launch-capable nation in 2009,[429] and is a founding member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. Iran placed its domestically built satellite Omid into orbit on the 30th anniversary of the Revolution, in 2009,[430] through its first expendable launch vehicle Safir. It became the 9th country capable of both producing a satellite and sending it into space from a domestically made launcher.[431] Simorgh's launch in 2016, is the successor of Safir.[432]

In January 2024, Iran launched the Soraya satellite into its highest orbit yet (750 km),[433][434] a new space launch milestone for the country.[435][436] It was launched by Qaem 100 rocket.[437][438] Iran also successfully launched 3 indigenous satellites, The Mahda, Kayan and Hatef,[439] into orbit using the Simorgh carrier rocket.[440][441] It was the first time in country's history that it simultaneously sent three satellites into space.[442][443] The three satellites are designed for testing advanced satellite subsystems, space-based positioning technology, and narrowband communication.[444]

In February 2024, Iran launched its domestically developed imaging satellite, Pars 1, from Russia into orbit.[445][446] This was the second time since August 2022, when Russia launched another Iranian remote-sensing, Khayyam satellite, into orbit from Kazakhstan, reflecting deep scientific cooperation between the countries.[447][448]

Telecommunication

Iran's telecommunications industry is almost entirely state-owned, dominated by the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI). As of 2020, 70 million Iranians use high-speed mobile internet. Iran is among the first five countries which have had a growth rate of over 20 percent and the highest level of development in telecommunication.[449] Iran has been awarded the UNESCO special certificate for providing telecommunication services to rural areas.

Globally, Iran ranks 75th in mobile internet speed and 153rd in fixed internet speed.[450]

Demographics

Iran's population grew rapidly from about 19 million in 1956 to about 85 million by February 2023.[451] However, Iran's fertility rate has dropped dramatically, from 6.5 children born per woman to about 1.7 two decades later,[452][453][454] leading to a population growth rate of about 1.39% as of 2018.[455] Due to its young population, studies project that the growth will continue to slow until it stabilises around 105 million by 2050.[456][457][458]

Iran hosts one of the largest refugee populations, with almost one million,[459] mostly from Afghanistan and Iraq.[460] According to the Iranian Constitution, the government is required to provide every citizen with access to social security, covering retirement, unemployment, old age, disability, accidents, calamities, health and medical treatment and care services.[461] This is covered by tax revenues and income derived from public contributions.[462]

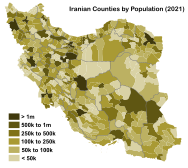

The country has one of the highest urban growth rates in the world. From 1950 to 2002, the urban proportion of the population increased from 27% to 60%.[463] Iran's population is concentrated in its western half, especially in the north, north-west and west.[464]

Tehran, with a population of around 9.4 million, is Iran's capital and largest city. The country's second most populous city, Mashhad, has a population of around 3.4 million, and is capital of the province of Razavi Khorasan. Isfahan has a population of around 2.2 million and is Iran's third most populous city. It is the capital of Isfahan province and was also the third capital of the Safavid Empire.

Largest cities or towns in Iran

2016 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Tehran  Mashhad |

1 | Tehran | Tehran | 8,693,706 | 11 | Rasht | Gilan | 679,995 |  Isfahan  Karaj |

| 2 | Mashhad | Razavi Khorasan | 3,001,184 | 12 | Zahedan | Sistan and Baluchestan | 587,730 | ||

| 3 | Isfahan | Isfahan | 1,961,260 | 13 | Hamadan | Hamadan | 554,406 | ||

| 4 | Karaj | Alborz | 1,592,492 | 14 | Kerman | Kerman | 537,718 | ||

| 5 | Shiraz | Fars | 1,565,572 | 15 | Yazd | Yazd | 529,673 | ||

| 6 | Tabriz | East Azarbaijan | 1,558,693 | 16 | Ardabil | Ardabil | 529,374 | ||

| 7 | Qom | Qom | 1,201,158 | 17 | Bandar Abbas | Hormozgan | 526,648 | ||

| 8 | Ahvaz | Khuzestan | 1,184,788 | 18 | Arak | Markazi | 520,944 | ||

| 9 | Kermanshah | Kermanshah | 946,651 | 19 | Eslamshahr | Tehran | 448,129 | ||

| 10 | Urmia | West Azarbaijan | 736,224 | 20 | Zanjan | Zanjan | 430,871 | ||

Ethnic groups

Ethnic group composition remains a point of debate, mainly regarding the largest and second largest ethnic groups, the Persians and Azerbaijanis, due to the lack of Iranian state censuses based on ethnicity. The World Factbook has estimated that around 79% of the population of Iran is a diverse Indo-European ethno-linguistic group,[465] with Persians (including Mazenderanis and Gilaks) constituting 61% of the population, Kurds 10%, Lurs 6%, and Balochs 2%. Peoples of other ethnolinguistic groups make up the remaining 21%, with Azerbaijanis constituting 16%, Arabs 2%, Turkmens and other Turkic tribes 2%, and others (such as Armenians, Talysh, Georgians, Circassians, Assyrians) 1%.

The Library of Congress issued slightly different estimates: 65% Persians (including Mazenderanis, Gilaks, and the Talysh), 16% Azerbaijanis, 7% Kurds, 6% Lurs, 2% Baloch, 1% Turkic tribal groups (including Qashqai and Turkmens), and non-Iranian, non-Turkic groups (including Armenians, Georgians, Assyrians, Circassians, and Arabs) less than 3%.[466][467]

Languages

Most of the population speaks Persian, the country's official and national language.[468] Others include speakers of other Iranian languages, within the greater Indo-European family, and languages belonging to other ethnicities. The Gilaki and Mazenderani languages are widely spoken in Gilan and Mazenderan, northern Iran. The Talysh language is spoken in parts of Gilan. Varieties of Kurdish are concentrated in the province of Kurdistan and nearby areas. In Khuzestan, several dialects of Persian are spoken. South Iran also houses the Luri and Lari languages.

Azerbaijani, the most-spoken minority language in the country,[469] and other Turkic languages and dialects are found in various regions, especially Azerbaijan. Notable minority languages include Armenian, Georgian, Neo-Aramaic, and Arabic. Khuzi Arabic is spoken by the Arabs in Khuzestan, and the wider group of Iranian Arabs. Circassian was also once widely spoken by the large Circassian minority, but, due to assimilation, no sizable number of Circassians speak the language anymore.[470][471][472][473]

Percentages of spoken language continue to be a point of debate, most notably regarding the largest and second largest ethnicities in Iran, the Persians and Azerbaijanis. Percentages given by the CIA's World Factbook include 53% Persian, 16% Azerbaijani, 10% Kurdish, 7% Mazenderani and Gilaki, 7% Luri, 2% Turkmen, 2% Balochi, 2% Arabic, and 2% the remainder Armenian, Georgian, Neo-Aramaic, and Circassian.[474]

Religion

| Religion | Percent | Number |

| Muslim | 99.4% | 74,682,938 |

| Christian | 0.2% | 117,704 |

| Zoroastrian | 0.03% | 25,271 |

| Jewish | 0.01% | 8,756 |

| Other | 0.07% | 49,101 |

| Undeclared | 0.4% | 265,899 |

Twelver Shia Islam is the state religion, to which 90–95% of Iranians adhere;[476][477][478][479] about 5–10% are in the Sunni and Sufi branches of Islam.[480] 96% of Iranians believe in Islam, but 14% identify as not religious.[481][page needed]

There is a large population of adherents to Yarsanism, a Kurdish indigenous religion, estimated to be over half a million to one million followers.[482][483][484][485][486] The Baháʼí Faith is not officially recognised and has been subject to official persecution.[487] Since the Revolution, the persecution of Baháʼís has increased.[488][489] Irreligion is not recognised by the government.

Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and the Sunni branch of Islam are officially recognised by the government and have reserved seats in the Parliament.[490] Iran is home to the largest Jewish community in the Muslim World and the Middle East, outside of Israel.[491][492] Around 250,000 to 370,000 Christians reside in Iran, and Christianity is the country's largest recognised minority religion, most are of Armenian background, as well as a sizable minority of Assyrians.[493][494][495][496] The Iranian government has supported the rebuilding and renovation of Armenian churches, and has supported the Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran. In 2019, the government registered the Vank Cathedral, in Isfahan, as a World Heritage Site. Currently three Armenian churches in Iran have been included in the World Heritage List.[497][498]

Education

Education is highly centralised. K–12 is supervised by the Ministry of Education, and higher education is supervised by the Ministry of Science and Technology. Literacy among people aged 15 and older was 86% as of 2016[update], with men (90%) significantly more educated than women (81%). Government expenditure on education is around 4% of GDP.[499]

The requirement to enter into higher education is to have a high school diploma and pass the Iranian University Entrance Exam. Many students do a 1–2-year course of pre-university.[500] Iran's higher education is sanctioned by different levels of diplomas, including an associate degree in two years, a bachelor's degree in four years, and a master's degree in two years, after which another exam allows the candidate to pursue a doctoral programme.[501]

Health

Healthcare is provided by the public-governmental system, the private sector, and NGOs.[503]

Iran is the only country in the world with a legal organ trade.[504] Iran has been able to extend public health preventive services through the establishment of an extensive Primary Health Care Network. As a result, child and maternal mortality rates have fallen significantly, and life expectancy at birth has risen. Iran's medical knowledge rank is 17th globally, and 1st in the Middle East and North Africa. In terms of medical science production index, Iran ranks 16th in the world.[505] Iran is fast emerging as a preferred destination for medical tourism.[361]

The country faces the common problem of other young demographic nations in the region, which is keeping pace with growth of an already huge demand for various public services. An anticipated increase in the population growth rate will increase the need for public health infrastructures and services.[506] About 90% of Iranians have health insurance.[507]

Culture

Art

Iran has one of the richest art heritages in history and been strong in many media including architecture, painting, literature, music, metalworking, stonemasonry, weaving, calligraphy and sculpture. At different times, influences from neighbouring civilisations have been important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art.

From the Achaemenid Empire of 550–330 BC, the courts of successive dynasties led the style of Persian art, and court-sponsored art left many of the most impressive pieces that remain. The Islamic style of dense decoration, geometrically laid out, developed in Iran into an elegant and harmonious style, combining motifs derived from plants with Chinese motifs such as the cloud-band, and often animals represented at a smaller scale. During the Safavid Empire in the 16th century, this style was used across a variety of media, and diffused from the court artists of the king, most being painters.[509]

By the time of the Sasanians, Iranian art had a renaissance.[510] During the Middle Ages, Sasanian art played a prominent role in the formation of European and Asian mediaeval art.[511][512][513][514] The Safavid era is known as the Golden Age of Iranian art.[515] Safavid art exerted noticeable influences upon the Ottomans, the Mughals, and the Deccans, and was influential through its fashion and garden architecture on 11th–17th-century Europe.

Iran's contemporary art traces its origins to Kamal-ol-molk, a prominent realist painter at the court of the Qajar Empire who affected the norms of painting and adopted a naturalistic style that would compete with photographic works. A new Iranian school of fine art was established by him in 1928, and was followed by the so-called "coffeehouse" style of painting. Iran's avant-garde modernists emerged by the arrival of new western influences during World War II. The contemporary art scene originates in the late 1940s, and Tehran's first modern art gallery, Apadana, was opened in 1949 by Mahmud Javadipur, Hosein Kazemi, and Hushang Ajudani.[516] The new movements received official encouragement by the 1950s,[517] which led to the emergence of artists such as Marcos Grigorian.[518]

Architecture

The history of architecture in Iran dates back to at least 5,000 BC, with characteristic examples distributed over an area from what is now Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. The Iranians made early use of mathematics, geometry and astronomy in their architecture, yielding a tradition with structural and aesthetic variety.[519] The guiding motif is its cosmic symbolism.[520]

Without sudden innovations, and despite the trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it developed a recognizable style distinct from other regions of the Muslim world. Its virtues are "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivalled in any other architecture".[citation needed] In addition to historic gates, palaces, and mosques, the rapid growth of cities such as Tehran has brought a wave of construction. Iran ranks 7th among UNESCO's list of countries with the most archaeological ruins and attractions from antiquity.[521]

World Heritage Sites

Iran's rich culture and history is reflected by its 27 World Heritage Sites, ranking 1st in the Middle East, and 10th in the world. These include Persepolis, Naghsh-e Jahan Square, Chogha Zanbil, Pasargadae, Golestan Palace, Arg-e Bam, Behistun Inscription, Shahr-e Sukhteh, Susa, Takht-e Soleyman, Hyrcanian forests, the city of Yazd and more. Iran has 24 Intangible Cultural Heritage, or Human treasures, which ranks 5th worldwide.[522][523]

Weaving

Iran's carpet-weaving has its origins in the Bronze Age and is one of the most distinguished manifestations of Iranian art. Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and Iranian art. Persian rugs and carpets were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories. As such, they represent simultaneous lines of tradition, and reflect the history of Iran, Persian culture, and its various peoples. Although the term "Persian carpet" most often refers to pile-woven textiles, flat-woven carpets and rugs like Kilim, Soumak, and embroidered tissues like Suzani are part of the manifold tradition of Persian carpet weaving.

Iran produces three-quarters of the world's handmade carpets, and has 30% of export markets.[524][525] In 2010, the "traditional skills of carpet weaving" in Fars Province and Kashan were inscribed to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.[526][527][528] Within the Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its manifold designs.[529]

Carpets woven in towns and regional centres like Tabriz, Kerman, Ravar, Neyshabour, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns. Hand-woven Persian rugs and carpets have been regarded as objects of high artistic value and prestige, since they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers.

Literature

Iran's oldest literary tradition is that of Avestan, the Old Iranian sacred language of the Avesta, which consists of the legendary and religious texts of Zoroastrianism and the ancient Iranian religion.[530][531] The Persian language was used and developed through Persianate societies in Asia Minor, Central Asia, and South Asia, leaving extensive influences on Ottoman and Mughal literatures, among others. Iran has several famous mediaeval poets, notably Mawlana, Ferdowsi, Hafez, Sa'adi, Omar Khayyam, and Nezami Ganjavi.[532]

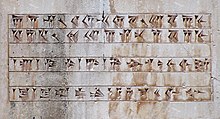

Described as one of the great literatures of humanity,[533] including Goethe's assessment of it as one of the four main bodies of world literature,[534] Persian literature has its roots in surviving works of Middle Persian and Old Persian, the latter of which dates back as far as 522 BCE, the date of the earliest surviving Achaemenid inscription, the Behistun Inscription. The bulk of surviving Persian literature, however, comes from the times following the Muslim conquest in c. 650 CE. After the Abbasids came to power (750 CE), the Iranians became the scribes and bureaucrats of the Islamic Caliphate and, increasingly, also its writers and poets. The New Persian language literature arose and flourished in Khorasan and Transoxiana because of political reasons, early Iranian dynasties of post-Islamic Iran such as the Tahirids and Samanids being based in Khorasan.[535]

Philosophy

Iranian philosophy can be traced back as far as Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts which originated in ancient Indo-Iranian roots and were influenced by Zarathustra's teachings. Throughout Iranian history and due to remarkable political and social changes such as the Arab and Mongol invasions, a wide spectrum of schools of thoughts showed a variety of views on philosophical questions, extending from Old Iranian and mainly Zoroastrianism-related traditions, to schools appearing in the late pre-Islamic era such as Manicheism and Mazdakism as well as post-Islamic schools.

The Cyrus Cylinder is seen as a reflection of the questions and thoughts expressed by Zoroaster and developed in Zoroastrian schools of the Achaemenid era.[536] Post-Islam Iranian philosophy is characterised by different interactions with the Old Iranian philosophy, the Greek philosophy and with the development of Islamic philosophy. The Illumination School and the Transcendent Philosophy are regarded as two of the main philosophical traditions of that era in Iran. Contemporary Iranian philosophy has been limited in its scope by intellectual repression.[537]

Mythology and folklore

Iranian mythology consists of ancient Iranian folklore and stories of extraordinary beings reflecting on good and evil (Ahura Mazda and Ahriman), actions of the gods, and the exploits of heroes and creatures. The tenth-century Persian poet, Ferdowsi, is the author of the national epic known as the Shahnameh ("Book of Kings"), which is for the most part based on Xwadāynāmag, a Middle Persian compilation of the history of Iranian kings and heroes,[538] as well as the stories and characters of the Zoroastrian tradition, from the texts of the Avesta, the Denkard, the Vendidad and the Bundahishn. Modern scholars study the myths to shed light on the religious and political institutions of not only Iran but of the Greater Iran, which includes regions of West Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, and Transcaucasia where the culture of Iran has had significant influence.

Storytelling has a significant presence in Iranian folklore and culture.[539] In classical Iran, minstrels performed for their audiences at royal courts and in public theatres.[540] A minstrel was referred to by the Parthians as gōsān, and by the Sasanians as huniyāgar.[541] Since the Safavid Empire, storytellers and poetry readers appeared at coffeehouses.[542][543] After the Iranian Revolution, it took until 1985 to found the MCHTH (Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts),[544] a now heavily centralised organisation, supervising all kinds of cultural activities. It held the first scientific meeting on anthropology and folklore in 1990.[545]

Museums

The National Museum of Iran in Tehran is the country's most important cultural institution. As the first and biggest museum in Iran, the institution includes the Museum of Ancient Iran and the Museum of the Islamic Era. The National Museum is the world's most important museum in terms of preservation, display and research of archaeological collections of Iran,[546] and ranks as one of the few most prestigious museums globally in terms of volume, diversity and quality of its monuments.[547]

There are many other popular museums across the country such as the Golestan Palace (World Heritage Site), The Treasury of National Jewels, Reza Abbasi Museum, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Sa'dabad Complex, The Carpet Museum, Abgineh Museum, Pars Museum, Azerbaijan Museum, Hegmataneh Museum, Susa Museum and more. Around 25 million people visited the museums in 2019.[548][549]

Music and dance

Iran is the apparent birthplace of the earliest complex instruments, dating to the third millennium BC.[550] The use of angular harps have been documented at Madaktu and Kul-e Farah, with the largest collection of Elamite instruments documented at Kul-e Farah. Xenophon's Cyropaedia mentions singing women at the court of the Achaemenid Empire. Under the Parthian Empire, the gōsān (Parthian for 'minstrel') had a prominent role.[551][552]

The history of Sasanian music is better documented than earlier periods and is especially more evident in Avestan texts.[553] By the time of Khosrow II, the Sasanian royal court hosted prominent musicians, namely Azad, Bamshad, Barbad, Nagisa, Ramtin, and Sarkash. Iranian traditional musical instruments include string instruments such as chang (harp), qanun, santur, rud (oud, barbat), tar, dotar, setar, tanbur, and kamanche, wind instruments such as sorna (zurna, karna) and ney, and percussion instruments such as tompak, kus, daf (dayere), and naqare.

Iran's first symphony orchestra, the Tehran Symphony Orchestra, was founded in 1933. By the late 1940s, Ruhollah Khaleqi founded the country's first national music society and established the School of National Music in 1949.[554] Iranian pop music has its origins in the Qajar era.[555] It was significantly developed since the 1950s, using indigenous instruments and forms accompanied by electric guitar and other imported characteristics. Iranian rock emerged in the 1960s and hip hop in the 2000s.[556][557]

Iran has known dance in the forms of music, play, drama or religious rituals since at least the 6th millennium BC. Artifacts with pictures of dancers were found in archaeological prehistoric sites.[558] Genres of dance vary depending on the area, culture, and language of the local people, and can range from sophisticated reconstructions of refined court dances to energetic folk dances.[559] Each group, region, and historical epoch has specific dance styles associated with it. The earliest researched dance from historic Iran is a dance worshipping Mithra. Ancient Persian dance was significantly researched by Greek historian Herodotus. Iran was occupied by foreign powers, causing a slow disappearance of heritage dance traditions.

The Qajar period had an important influence on Persian dance. In this period, a style of dance began to be called "classical Persian dance". Dancers performed artistic dances in court for entertainment purposes such as coronations, marriage celebrations, and Norouz celebrations. In the 20th century, the music came to be orchestrated and dance movement and costuming gained a modernistic orientation to the West.

Fashion and clothing

The exact date of the emergence of weaving in Iran is not yet known, but it is likely to coincide with the emergence of civilisation. Ferdowsi and many historians have considered Keyumars to be first to use animals' skin and hair as clothing, while others propose Hushang.[560] Ferdowsi considers Tahmuras to be a kind of textile initiator in Iran. The clothing of ancient Iran took an advanced form, and the fabric and colour of clothing became very important. Depending on the social status, eminence, climate of the region and the season, Persian clothing during the Achaemenian period took various forms. This clothing, in addition to being functional, had an aesthetic role.[560]

Cinema, animation and theatre

A third-millennium BC earthen goblet discovered at the Burnt City in southeast Iran depicts what could be the world's oldest example of animation.[562] The earliest attested Iranian examples of visual representations, however, are traced back to the bas-reliefs of Persepolis, the ritual centre of the Achaemenid Empire.[563]

The first Iranian filmmaker was probably Mirza Ebrahim (Akkas Bashi), the court photographer of Mozaffar-ed-Din of the Qajar Empire. Mirza Ebrahim obtained a camera and filmed the Qajar ruler's visit to Europe. In 1904, Mirza Ebrahim (Sahhaf Bashi) opened the first public cinema in Tehran.[564] The first Iranian feature film, Abi and Rabi, was a silent comedy directed by Ovanes Ohanian in 1930. The first sound one, Lor Girl, was produced by Ardeshir Irani and Abd-ol-Hosein Sepanta in 1932. Iran's animation industry began by the 1950s and was followed by the establishment of the influential Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults in 1965.[565][566] With the screening of the films Qeysar and The Cow, directed by Masoud Kimiai and Dariush Mehrjui respectively in 1969, alternative films set out to establish their status in the film industry and Bahram Beyzai's Downpour and Nasser Taghvai's Tranquility in the Presence of Others followed. Attempts to organise a film festival, which had begun in 1954 within the Golrizan Festival, resulted in the festival of Sepas in 1969. It also resulted in the formation of Tehran's World Film Festival in 1973.[567]

Following the Cultural Revolution, a new age emerged in Iranian cinema, starting with Long Live! by Khosrow Sinai and followed by other directors, such as Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi. Kiarostami, an acclaimed director, planted Iran firmly on the map of world cinema when he won the Palme d'Or for Taste of Cherry in 1997.[569] The presence of Iranian films in prestigious international festivals, such as Cannes, Venice and Berlin, attracted attention to Iranian films.[570] In 2006, 6 films represented Iranian cinema at Berlin; critics considered this a remarkable event in Iranian cinema.[571][572] Asghar Farhadi, an Iranian director, has received a Golden Globe Award and two Academy Awards, representing Iran for Best Foreign Language Film in 2012 and 2017, with A Separation and The Salesman.[573][574][575] In 2020, Ashkan Rahgozar's "The Last Fiction" became the first representative of Iranian animated cinema in the competition section, in Best Animated Feature and Best Picture categories at the Academy Awards.[576][577][578][579]